Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6 part I

Chapter 6 part 2

Chapter 7

Chapter 8 part 1

Chapter 8 part 2

Chapter 9 part 1

Chapter 9 part 2

Chapter 10 part 1

THREE WOMEN WERE TALKING by the terrace door; they turned as we entered. “Venustia!” They greeted my grandmother as if they hadn’t seen her for weeks. It had probably been days at the most, I thought wryly. “Who is this?” one asked.

“My granddaughter Eudekia.” A hand, lightly, on my shoulder, propelling me forward. Introduction were made. I smiled, and said the appropriate things; the polite chatter came easily to me now. Except that I could not turn it to business after a few sentences, or even to a discussion of philosophy or history. Or could I?

The chance I needed came quickly; sipping her wine, one of the women asked about my father. “A tutor to the prince, I understand?”

“He is,” I said. “It is why he is not here. Being the prince’s tutor is an honour, but a demand on my father’s time, too. I have taken over his duties as patron, largely.”

“Have you?” A look of surprise—or perhaps shock?—crossed the woman’s face. “Surely a secretary could have done that.”

“My father asked me to,” I said, “and I was pleased to do it.”

“But you must meet and speak to tradesmen.”

“Some of whom are interesting,” I answered, with a smile. “Especially the merchants, who have stories of far lands and cities.” I gestured to her tunic. “I could tell you how far the silk that trims your sleeves has travelled, and how, if you would like to know.”

The woman—I’d forgotten her name already—exchanged a look with another, eyebrows raised. They were nearly interchangeable, of similar height and age and hair style. Sisters, perhaps? The third woman, Seia, studied me. I met her eyes. She gave me a nod, a tiny smile playing on her lips. I remembered her; last time we’d visited, she’d asked me about my lessons in a way that wasn’t just polite. “I hope you are not neglecting poetry for commerce now,” she said.

“Not for commerce, no,” I said, “but for philosophy instead.”

“And do you agree that philosophy is morally superior to poetry, because one is truth and one illusion?”

“If philosophy were truth,” I said, “all philosophers would agree. They do not.”

She laughed. “I cannot counter that.”

“And,” I added, caught up in the argument, “we comprehend both philosophy and poetry through our own experiences. How can we know what we take from the words is what the author wished to convey? Especially if we read the work in translation from another language.”

“A very good point,” Seia said.

“Is this what your father has you study, when you are not dealing with his business interests?” The question came from one of the other two women, the one who wore a blue shawl. “What of the arts of managing a household?”

“Eudekia has been adept at that for several years,” my grandmother said. “Not all women need do nothing else.” Her eyes slid to Seia as she spoke. In solidarity, I thought, as we took our places for the meal.

The conversation as we ate was light, of a new musician at one villa, the birth of a great-grandchild, the grape harvest. “What news of your grandson, Seia?” blue shawl asked, dipping her fingers into the small bowl of water in front of her. The pastries had been sticky with honey.

“Posted east,” Seia said. “To Qipërta, for which I am glad. The border is quiet there.”

“No doubt he’d have preferred to see action,” green shawl said. Even her voice was the same. They must be sisters, I decided.

Seia made a face. “Young men do.”

“Was it a recent posting?” I asked. “I saw warships sailing east this morning when I was out riding.”

“Then he was likely on one of them.” She turned to my grandmother. “An excellent meal, Venustia. May I have Eudekia show me the gardens?”

Gardens which she had seen a hundred times, I was sure. But there was no polite way to refuse, and at least it was Seia, not one of the shawled sisters.

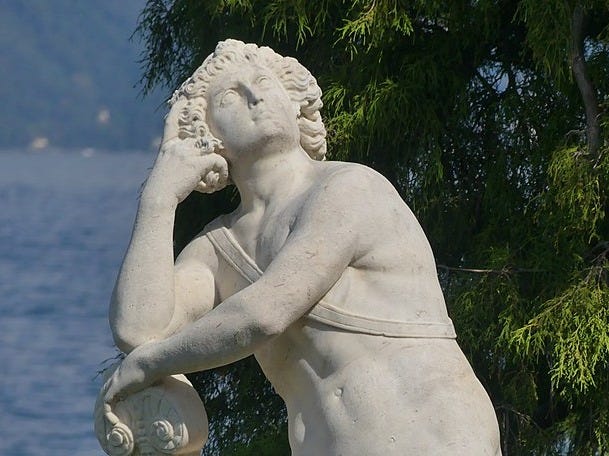

We walked along the paths of crushed shells, firm underfoot. “Look how beautifully that vine frames the wine god,” Seia said. The statue overlooked the grape terraces, the leaves of the vine trained around the feet of the god and up and over a marble shoulder.

“If the workers look up, they see the god in his mountain glade,” I said.

“You know Pronus?”

“Some of the odes,” I said, pleased she’d caught the reference to the poet’s hymn to the god.

“Do you write poetry?”

“Me?” I glanced at her in surprise. “No. Although my tutor insists the translations he sets me must both convey the idea of the original, and have a pleasing cadence.”

“A good way to learn how to shape words and meaning. A skill worth refining, for both men and women. Perhaps you should try with your own thoughts.”

Something in the way she spoke made me ask. “Do you?”

“I do.” She smiled, her eyes distant. “My husband was active in the Assembly and at the palace, but he had little subtlety with words. I helped him write his speeches and letters, with fair success. When he died, I began to write for my own purposes, liking the concentration of the mind and the discipline of poetical structure in expressing my thoughts.”

“I am glad it gives you pleasure, domina,” I said.

“As am I,” Seia said. “But I did ensure my sons, and theirs as well, were proficient with language, both written and spoken. My youngest grandson is a good poet already, and a fine speaker.”

“The one who has just been posted to Qipërta?”

“Yes. Your grandmother has suggested he be proposed to your father, and having met you, I think it appropriate.”

The cold of shock suffused me as her words sank in. I stared at Seia, incapable of speech.

“I know you have no wish to marry now,” the woman said. “But my grandson’s new posting will be for two years.”

“But—” My voice didn’t work. I swallowed, tried again. “But I haven’t met him.”

“That is not unusual, you know.” She sounded amused. “I assure you he is presentable, and as well-mannered as he is well-educated. His hair is as dark as mine was once, but he has his mother’s blue eyes, and,” she gave me an assessing look, “he is taller than you, by half a handspan.”

“I see,” was all I could manage to say. She seemed neither surprised nor put out by my silence. We resumed walking. Ahead of us was another statue, this one of the sun god in all his unclothed, radiant glory.

I’d seen the statue—and others like it—since earliest childhood. Why couldn’t I look at it now?

~~~

When the guests left, I pleaded a headache from the sun and went to my room. My thoughts swirled like fallen leaves in the winds of autumn, settling for a moment only to take flight again. Why hadn’t my father told me why I had been sent here? He’d given me a false reason. No wonder he’d entrusted his letter to my grandmother with Nishan.

I knew this was how things were done. It was how Ennaia had been chosen for Kaeso, the two then given the usual half-year to determine their compatibility. Would I be given that in two years’ time when Seia’s grandson returned from Qipërta?

I would demand it. It was my right, although many girls did not bother, or did not take the full time. Ennaia had declared herself happy to marry Kaeso after less than a month. Almost as soon as she had bedded him, I remembered. But she’d always had far more interest in the delights of the body than I.

I wished there was someone I could talk to. But even if I wrote Ennaia a letter, she wouldn’t understand my reluctance. Seia’s grandson, a young officer of the dignitasi, was a good match. Our families were friends, and Seia had taken pains to let me know we shared interests.

But probably not as many as Philitos and I shared.

I could write to him, I thought. But he wouldn’t understand either: he had to marry for diplomacy and politics.

I couldn’t settle. I paced the room, the headache I had claimed becoming real. I heard Matea’s quiet knock at the door. Good. I would send her for willowbark. “Come in,” I called.

It wasn’t Matea. My grandmother stepped in, closing the door firmly behind her.

“Child,” she said, “why are you so upset? And sit down, please. I cannot talk to you while you pace.”

A start of anger almost forced words I’d regret from me. But she was a good listener, and hadn’t I just been wishing for someone to talk to? I sat on the bed, drawing my legs up under me.

“Why wasn’t I told I was here to be displayed?” I said. Two small lines appeared between my grandmother’s eyes.

“What reason did your father give for your visit here?”

“That he was worried about you.”

“How ridiculous,” she said. “Renatus, I assume?” I nodded. “That is no one’s business except mine. What a fool my son is, sometimes. He is letting his palace appointment go to his head.”

“He has been ill,” I said. “And...”

“And?”

“And the fault could be mine. When he first became ill, I asked him what would happen to me if he died. He said I would come to you, and maybe he was—”

“Thinking a woman who took her steward to her bed was not fit to oversee a grown granddaughter?” She gave a bark of laughter. “Nonsense. If he thought that, he would not have sent you here now. Use your brain, child.” She sighed, but I thought it was exasperation directed at my father, not me. “You are nineteen, Eudekia. Most girls are married by your age. Is it the physical side of marriage that makes you reluctant? Are men not to your taste?”

“It’s not that.” I knew, from my own explorations, what pleasure a body could give, and I knew what happened between a man and a woman. We had pots in the atrium with scenes of gods consorting with mortals, and I’d read some of Valerias’s poems—although secretly. And once Ennaia was no longer virgin, I’d had an even better idea. But her descriptions hadn’t made me feel much.

“Then what is it? Seia’s grandson is sought after; he has prospects, and a good family.”

I couldn’t explain. I didn’t know why. Unthinkingly I reached for the bronze cat, which sat on the table beside the bed. I ran a finger along it.

“What’s that? May I see?” My grandmother only sounded interested. I held the cat out to her.

“How lovely! Where did you get it?” She smiled at the little figure before handing it back.

“Philitos gave it to me.”

“The prince?” Her voice was sharp. I nodded. Her eyes narrowed. But when she spoke again, it was gently. “Eudekia, you have written to him once already. Tell me, do you look at things—say the view from the hilltop—and want him to see it? Do you taste the food, and consider if he would like it or not?”

I had done all this. “Yes.”

“Why?”

“He’s my friend.”

“Oh, child. Did you ever think like this about your female friends?” She shook her head, smiling. “Let me tell you why you are here. The Emperor asked your father to send you away.”

I stared at her. “Send me away? Why?”

“Because the prince is, in his words, infatuated with you. But that is only a word parents use when they disapprove of their children’s choices. Philitos is in love, and I think you are too.”

“But I can’t be.”

She laughed, but it wasn’t mocking. “Why ever not?”

“He’s the prince. He has to marry for politics.”

“And he may. But what has that to do with being in love?” She reached out to take my hand. “Indulge me for a minute, Eudekia. Pretend it was Philitos who had been proposed as your husband today, not Seia’s grandson. Is your reaction the same?”

I closed my eyes, to make the imagining easier. I saw Philitos sharing a meal with me, playing xache, discussing books. It felt—comfortable. But there was more to marriage than that. I thought about the things Ennaia had described, tried to envision Philitos’s touch—and caught my breath at the sensation that shot through me. I heard my grandmother laugh.

“Your face said it all, child.” I opened my eyes, heat rising in my cheeks. “Don’t blush! You have nothing to be ashamed of. He is a handsome man, from all I have heard.”

“Yes,” I said, and then, without knowing I was going to, I started to cry.

Pronus’s odes to the forest god are analogues of Virgil’s odes to Silvanus, and the poetry that Eudekia (secretly and wide-eyed) read by Valerias are analogues of Martial’s epigrams, which are, as Steve Coates, writing in the New York Times, put it: ‘Even by today’s standards… grotesquely obscene.’

Monday Dec 2 is the last day of this $1 or less sale: https://books.bookfunnel.com/blackfridayblast/bpmmp5g82l

Discover more of the extended world of Druisius and Eudekia (for free!) here

Impatient to read more? Find Empress & Soldier HERE

Check out a wide range of free offerings at: https://go.bookmotion.pro/genreallstars/yu8jbboadh

Yes, I definitely like grandma, astute and sympathetic.