If you’re new to the serialization of Empress & Soldier, the full table of contents follows the first chapter.

If you just need reminding of last week’s post, or to catch up on one or two, use the Previous/Next buttons at the very end of each week’s posts.

The day will be hot, but the sun has not reached these narrow streets yet. I want to run, or lift heavy things. Something to expend the energy coursing through me. But I am clumsy, too, like a crewman new to the sea. I grin to myself, and walk towards the smell of cooking drifting down the alley.

At the cookstall I eat fresh bread and figs, and drink water tasting of vinegar, sharp on my tongue. I have work today, questions to ask, but it is too early. I could go back to our rooms. But there will be little to do, and I have nothing yet to report.

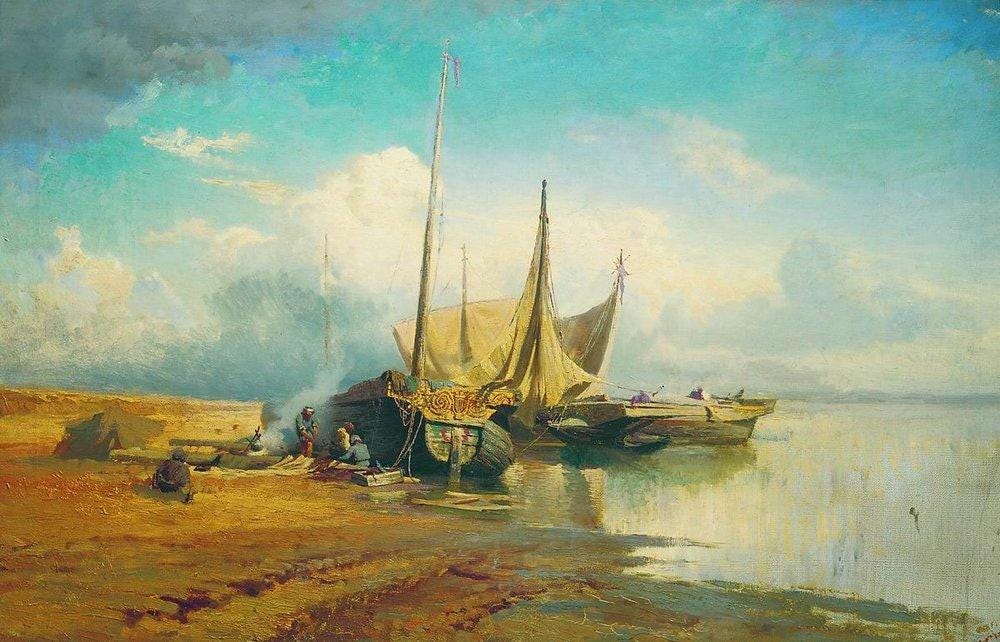

Instead, I walk. Randomly, I think, until I see the line of gulls on the city wall. The gate is open, carts entering. Beyond them, the jetties, barges unloading and loading. The gate guard asks my business. I show him my insignia. “Off duty,” I tell him.

He gestures me through. This is a river port, not the wide basin of Casil’s harbour. But more similarities than differences. Warehouses, shouts, the lap of water on stone. I walk along the quay. A long boat, flat bottomed, laden, is coming in. A boy of about twelve stands on the thwart, rope in hand. The boat comes closer to its mooring. He jumps for the quay, to pull it in.

And misses, by half his body length. He goes under, surfaces, splutters, goes under again. The man on the boat shouts. I run, three paces, dive off the quay. Hope the water is deep.

It is. I swim a stroke or two, grab the boy, hoist him up. I can stand, just, the water at my chin. He is holding on tightly, hurting me, but he cannot know. I make the quay, and he scrambles up. I follow, pushing up with my arms, getting one knee onto the stone and then the other. The boy is sitting, panting a little. I tie up the boat, the motions made without thought.

“Thank you,” the man on the boat calls. I wipe water from my face and hair.

“What the fuck were you doing?” he asks the boy. Fear fuels his anger.

“I’ve done the same,” I say, grinning down at the boy. I haven’t, but the lie is harmless.

The man grunts. He eyes me. “You’ve tied up a few boats before, I’d say. Merchant, are you?”

I shake my head. “Supposed to be. Joined the army instead. At sixteen, yes?”

The boy has jumped down into the barge now. He is untying the nets that cover the cargo. The man cocks his head. “From Casil? Or the southern lands?”

“Casil.” My tunic and leggings drip water. I run my hands over them, pushing out as much as I can. “Need a hand unloading?”

“I won’t say no.”

We unload bundles of fleeces and hides, then, from under a section of decking, cheeses. Kept below the waterline, to be cool. The boy hands the rounds up, one by one. The man chats as we work. They are from upriver, where the mountain villages graze animals. He makes the trip down to Serdik every few months, more when the sheep have been sheared and there is wool to bring.

My clothes dry as the sun’s heat strengthens, and in the breeze off the river. I wait, sitting on the edge of the quay, as the warehouseman inspects the cargo and the necessary documents are signed. The boy sits beside me.

“Have you really fallen in the water too?” he asks, suddenly.

I repeat my earlier lie. Then I tell him I saw a man crushed once, when he misjudged his jump at Casil’s harbour. Only one small sail on the ship, but the wind caught it, pushed the vessel into the quay. Too quick for boathooks or spars. “Learn to swim,” I add. That he cannot surprises me, but what do I know of the customs of mountain people here?

“What’s your name?” he asks.

“Druisius. Yours?”

“Malki.” Cub, in the local language. “Until I am a man,” he adds. “Then a new one.”

I grin. “If you learn to swim, maybe it will be Fish.” He laughs. The man comes over to us. “We’re done. Let’s find some ale. Malki, stay with the boat.” The boy’s face crumples.

“Must I, uncle?”

“Can’t just leave it, can I?” the man says. Malki scuffs his foot along the ground, head hanging.

“Wait.” I look up and down the quay. One of the guards leans against a warehouse wall. I whistle. He looks up, saunters over.

“And who the fuck are you to be calling me like that?” But I am ahead of him, my sergeant’s insignia pinned now to my tunic. He sees it. Pales. Straightens. “My apologies, Sergeant.”

I look him up and down. Letting him be afraid. “Your name, idiot?” I say. In my best sergeant’s voice.

He gives it, and without me asking, his capora’s. Willing to take what comes. “You’re not paid to lean against walls,” I say. “Keep an eye on this boat while we’re gone.” He salutes. Inside, I laugh. Sergeants are not paid to unload boats, either. But he cannot say that.

The man says nothing until we are through the city gates. “I hadn’t taken you for an officer.”

“More like the warehouse foreman, yes? Men report to me, but I take my orders from my captain.” He nods his understanding.

We do not go far. The man knows the taberna he wants, open to the street. Stools and a counter, its surface covered with random scraps of marble. I run fingers over one or two, recognizing the stone. The boy looks around, at people, at carts, at pictures painted on shopfronts, obscenities scrawled on walls. His first time in Serdik, I guess. I accept the ale, thin and sour. Malki gets half a cup, watered.

I can feel the throb of bruises again now. The man drinks. “Thanks again,” he says.

I shrug. “I like the docks.” I swallow some more ale. “You get a fair price for your goods?”

“Good enough. Worth making the trip.”

“What are the harbour fees like now?” I can speak this language. As easy as the army’s. Maybe easier.

He grimaces. “Steep, but no change this year. Warehouse charges the same, too. And the boy’s an apprentice, so I’m not paying a hand.”

“If he doesn’t drown,” I say. Malki looks up, grins.

“If,” the man agrees. “And there’s not usually a bored sergeant at the quayside, but I can always find someone who’ll help unload for a few coins.”

I raise my cup. “Ale’s enough for me.” I finish the cup, stand. Hold out a hand. “Think I’ll try proper baths now.”

We shake hands. The boy offers me his, solemnly. I take it, so small in mine. “Remember what I said,” I tell him.

“I will,” he promises.

The sun is high now. I am going to the baths, but not to soak.

Find all my books here.