Find the table of contents/links to earlier chapters here.

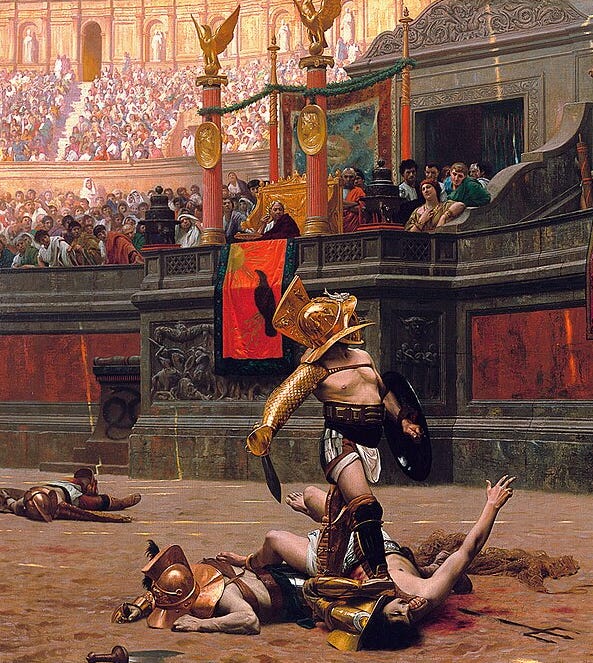

I would have rather discussed the supplies of grain than watched men and animals die, I decided. I’d have been glad of the distraction, although I’d done what was expected of me and offered a symbolic wreath to the victor of the final pairing. He’d bowed to me from the bloodied sands as I held high the golden circle. A copper replica and a bag of coins awaited him. He’d fight again on the last day, and if he was victorious again, he was free of the games, Philitos told me.

“What will he do?” I asked, curious.

“Buy a taberna or a shop, most of them. Some get hired as private guards at the warehouses and the docks.”

One of the last things I’d granted as patrona, before I left the work to Mahir, was an advance to hire more guards at the harbour, the merchants worried about attempts to steal grain. This man wouldn’t have trouble finding employment, if that is what he wanted. I wondered if I could send him to the group of merchants who had approached me—but no. I was not their patrona now: I had to think of the good of all Casil, not just my father’s clients.

I had asked Philitos for one favour, a transfer for Kaeso to the tax department. He’d agreed without hesitation. It would still be a provincial appointment, but it would make Ennaia and her family happy, and some day she’d be back in the city. I missed her chatter, as unimportant as it was, or perhaps because it was. My private hours with Philitos aside, there wasn’t going to be much frivolity in an Empress’s life.

Nor anything resembling a regular working day, but I’d understood that from the hours my father had kept—still kept—at the palace. After the meal that had followed the games, with more dancers and musicians performing for the dignitasi invited to share our marriage feast, when I had spoken to a hundred people, been congratulated with varying levels of sincerity, and wanted nothing more than my bed and sleep, Philitos stood. “With me, please,” he said to his advisors.

I looked up at him, unsure. “And I?”

“Of course.” He held out his hand. “You are the Empress, my Eudekia. Your thoughts matter.”

We retired to what was clearly a workroom, furnished with a long table with many chairs. Shelves held bound records and rolls. Off to one side was a writing desk, and as we took seats a man entered through another door, taking up his position there. Philitos’s secretary, or one of several. I would have to learn his name.

“Tell us your concerns, Fiscarius,” Philitos spoke mildly. The secretary picked up his pen.

“They are two, and not unrelated,” Quintus said. “Grain harvests, as you know, are sparse this year throughout the empire, from drought and insects. The price of grain, and therefore bread, is high, and for the suburani and poorer, this is a problem. Hungry people are angry people, Emperor. In ten days, when the rations of free bread stop, I expect riots.”

Riots. I thought of what Philitos had told me of the one in Oppelorium. The rebels had burnt part of the city, and looted more. Even weeks later, shock had echoed in his voice when he’d told me about it. Did the memory disturb him now?

“What are your plans to counter that?”

“We have hired more guards for the city and palace, Emperor. The soldiers that relieved them of other duties today can be retained, but not indefinitely, the general tells me.”

“I worry about the borders,” Genucius replied. “Weakening our presence is to invite attack.”

“This drought is widespread,” I said. “Surely the Boranoi have the same problems, if not worse. They have no access to grain from the lands across the Nivéan Sea.”

“All the more reason to attempt an invasion.” Genucius pointed out.

“There are traders who sell grain to the Boranoi. Or to merchants of Qipërta who act for the Boranoi.” My husband spoke gently, stating a fact, not correcting me, exactly. Of course there were; I should have realized that.

“A problem related to the troops, Emperor, is that they too must be fed.” Genucius nodded at Quintus’s words. “The rising price of grain affects your treasury, and it has borne much expense recently. The city built in Odïrya. Your late father’s last marriage, and the endowment of the temple when the princess returned to Qipërta. His funeral and the memorial games. Now your wedding with its necessary outlay.”

“Raise taxes,” Genucius muttered.

“No!” My father spoke with force. “Higher taxes take more food from the mouths of those who grow the grain and beans we need. Hunger means weakness and disease, and a spreading pestilence in the countryside would soon reduce the food supply even further.”

“Why are we spending money on games instead of food?” I reached for a lock of hair, touched the pearls entwined in it instead. Pearls and emeralds. How much grain would they buy?

“Because the people expect it, Empress,” Genucius said wearily.

“But would they not prefer to eat?”

“The common people do not understand finance, Empress,” Quintus said. “They expect both games and food.”

I did not like Quintus, I decided. I’d tried not to let my father’s reservations about him colour my own opinion, but I was beginning to understand them. Philitos had appointed Quintus fiscarius at the same time Genucius had taken over the military advisor’s role from the ailing Roscius. The man was too smooth, and his treatment of me fluctuated between condescending and flattering. Had anyone ever asked the ‘common people’? I thought the merchants I had dealt with as patrona might have a different opinion.

The men talked. The system of rationing that had been implemented to distribute the free bread during the celebrations would be kept in place after they were over. This would ensure a fair distribution—or at least an attempt. Bakers would be ordered to make the loaves smaller.

“We should set the price to no higher than it was before my father’s death,” Philitos said.

“Then we must pay the bakers a subsidy.” Quintus reached for the wine jug. The servants had been dismissed. He began to pour, then caught himself. “Emperor?” Philitos shook his head. “Empress?”

“A little,” I said, “and the water, please.” He half-filled my cup, then pushed the water jug across the table.

I sipped the wine. Still too strong; I would add more water after I’d drunk a little. Fatigue washed through me. I hadn’t slept well last night, and the long, public day was catching up with me. For a moment, I wished I were at home, sitting in the atrium watching the kittens eat the scraps the kitchen girl mixed up for them at the end of the day.

Watered wine. Meat scraps mixed with old bread. “Is there something the bakers can mix with the flour to make it go further?” I asked.

“Lentils and peas are also in short supply,” Quintus said.

“That’s not what I meant. Something that would make people feel full, even with less flour in the loaves.”

“An interesting idea,” my husband said. “Is this possible?”

“It could be,” Genucius said. “I have heard of people who grind bones into their flour.”

“Grape skins and seeds from wine making,” my father said. “It is spread back among the vines now, but a year or two without will not lessen the yield too greatly.”

“Quintus, find people to deal with this,” Philitos said. “Is that sufficient for tonight?”

“There is still the question of the depleted treasury.” An edge to Quintus’s voice. He hadn’t liked the task he’d just been given, I guessed.

“Bring me solutions tomorrow.” Philitos stood, holding out a hand to me. “Your Empress is tired. As am I. We will meet again mid-morning.”

I wished the men good night. They were on their feet, of course. My father caught my eye. “Good night, Empress.”

In the corridor, guards fell into step behind us. Torches and shadows flickered. We walked in silence.

Matea waited in our rooms. Philitos left me with her. Beyond our bedroom was a smaller room, furnished with a desk and a single bed: Philitos’s, for working late or early, and for sleeping when I was indisposed, he’d told me. But it also allowed him to wash and change when Matea was attending to me.

Taking my hair down took some time. I’d ask her to dress it simply tomorrow, I decided. The last of the jewels removed and the braids undone, she combed it gently, then rebraided it into one plait. The familiar attention soothed me, easing the sudden dislocation I’d felt at my father’s words. At some level I’d been playacting all day. His ‘Good night, Empress’ had been a stark reminder. I would not step off this stage to return to real life.

“You did well today,” Philitos said. Matea had just slipped a sleeping shift over my head. He stood watching, a loose robe belted around him, barefoot.

“Did I? Thank you, Matea. That’s all tonight.”

“Breakfast three hours after sunrise, please,” Philitos added. She bent a knee before leaving us.

I sat on the bed. “What do I do tomorrow?”

He looked puzzled. “Join me in meeting my advisors again, I hope.”

“If you like. But surely you don’t always want me there?”

“I do.” He sat beside me. “My father worked tirelessly almost to the day he died. I must be seen to do the same, and there is much to learn. I need your thoughts and observations, my Eudekia. Unless it is too much to ask?”

“Of course it’s not,” I said. He slipped an arm around my shoulders. I turned my mouth to his, desire conquering fatigue. In its aftermath, I slept without dreams.

Like what you read? Donations for my local foodbank are gratefully received.

Find all my books at https://scarletferret.com/authors/marian-l-thorpe

Free books! Including A Divided Duty, an introduction to my fictional world and some of its characters. Here, until May 17th, here until May 26th, here until June 2, 2025. and here until July 17.