Empress & Soldier: Chapter 2

In which Druisius learns what it is to be a soldier.

I DIP THE WET CLOTH into the bowl and smear wood ash on the buckle. I rub, rhythmically, humming a tune. In my head, I picture the fingering on the cithar that makes the notes. The sun is dropping to the west. It is pleasant still in the afternoon air.

I rinse the buckle, dry it with a different cloth. It shines. I am done. This is a daily task, here at the encampment, my few pieces, and Marcellus’s full armour. He will want the buckles soon. He, and all the officers, go to see the general at sunset. There are orders, he told me earlier.

Orders. Will we be going to war? I think so. The older men, the veterans, they say so. On the training field the sergeants are harsher, if that is possible. The officers talk, heads bent close together. Marcellus has said nothing to me, but I sense excitement. It spills over into what we do at night, or sometimes before dawn.

I grin at that thought. I saw the tall young officer supervising the troops at the docks that day. Knew why he watched me. Water from the storm puddled the quays. Crews bailed sodden ships. The soldiers had been sent to assess damage. Not much, here. Not like the river. Docks and barges gone, trees too. The shacks of the poor. In an alcove of a bridge, nothing but the stains of muddy water. My grin drops away. I will not think of that. It is past, done.

The officer had approached us as we unloaded amphorae. Marius and I worked with the warehousemen, my father watching as he conferred with the foreman. In the hot wet air, I had stripped off my tunic.

I had placed the amphora I carried in the cart, straightened. Watching the officer now. He caught my eyes. No smile, and yet. Something. I stretched, flexing my shoulders. A flicker, on his face. Then he turned to my father. “Is this your son?”

“Both are.”

“The older one. Is he sixteen?”

My father shook his head. “No. Fourteen. Too young, Captain.”

“I am not,” I said. Loudly. “It is a lie,” I added, walking to them. “A lie to save the head tax, when we came.” I had thought there might be fines. Something to punish my father.

The officer had looked from me to my father. “Is it?” he had asked. “I am inclined to think so. He does not look fourteen. He is too strong, too well-muscled.” He turned to me. “What is your name?”

“Druisius.”

“The army could use you, Druisius.” The army? I had not thought of that. I would go far from here.

My father had argued, but not much. Not once the officer mentioned inspectors, and tax records. “My patron is Varos,” he had challenged. The officer had barely raised an eyebrow.

“A good man. But a scholar. He will not involve himself in the recruitment of a young man to the troops.”

So here I am, emptying wet ashes and dirty water into the midden ditch. A foot-soldier, and aide to Captain Marcellus. His soldier-servant, who sleeps in his tent to be close if needed at any hour. The grin returns. I glance at the sun. I have a few minutes. Time to practice the cithar. Another thing the captain is teaching me.

“Druisius!” A soldier calls to me. “Come and dice.” Why not? I can practice the cithar later, when Marcellus is writing records. I am good enough now I will not disturb him with wrong notes.

I win a little, lose a little more. I know when to stop, though. “Marcellus needs me,” I say, standing to leave. The expected comments, but all officers have their servants. No one cares. After eight months on the training field, I am good with both swords, short and long. That is what matters.

I arrive at his tent just as he does too. He gives me a quick smile. “I haven’t time for the baths,” he says. “Bring me water, will you?” He washes hands and face and armpits.

“Should I shave you?” The camp’s barber has taught me how, at Marcellus’s request.

He runs a hand over his chin. “Not necessary.” I help with buckles and fasteners, until he stands in full uniform.

“Thank you,” he says. He is always polite. Well, not always, but that is different. I give him a comb to run through his dark hair, kept short for ease. He is from lands north of Casil, he has told me. His father grows fruit on the hillsides and grazes cattle. A big estate. He is the second son.

“We are going to war?” I ask, as I put away the comb. The inside of the tent is dim now, but not enough to need a lamp. Later, I will light a brazier against the cool of a spring night.

“I expect so.” He does not bother to tell me to say nothing. I know not to. I like my assignment. Better than the barracks tents, and he shares good wine.

“This evening I should go to see my wife,” he says. She lives, with their two children, in the town half an hour west of the camp. I have met her twice. “Alone, this time,” he adds. As I expected.

“You will be back for breakfast, yes?”

He spreads his hands. “I will know after the briefing. It will depend on how quickly we are to move out.”

I glance around the tent. If we are to move, then I will need to pack. “What do we take?”

He shakes his head. “I don’t know yet. It depends on where we are going.”

Maybe we go by ship, then? He should know, if it was to be marching and carts. I know he has not sailed. He tells me of his life, some nights. Tutors and music, hunting and the skills of debate, before the army. He has plans and expectations. I will rise with him, he says.

It is marching and carts, he tells me later. At least for most of the journey. There will be ships, at the end. We are going to Qipërta, a land to the east, across a wide arm of the Nivéan Sea. He shows me a map. Qipërta is a province of Casil, but the lands north of it belong to the Boranoi. We have an unquiet peace with the Boranoi, he explains, and they are making incursions into Qipërta. Our job will be to chase them out, and strengthen the border.

We are to leave at dawn, the day after tomorrow. I can pack all but essentials.

I go back to the tent, look around. What stays behind? A set of shelves where Marcellus keeps his books, the stool I use, the brazier. Or does it? A fine rug covers the canvas of the floor. It too will stay. I crouch by one of the chests, going through its contents. Warmer clothes—will those be needed? Qipërta is north of us, just a little.

If I get this wrong, Marcellus will not have what he needs. He will suffer, and it will be my fault. I am a good soldier-servant for him here at the training camp. All he needs is wine and food brought, the brazier lit, his armour polished. And a bedmate. These I can do.

If I get this wrong, will he send me back to the barracks, just another foot-soldier? I sit back on my heels, thinking. This is a test. If I am to rise with him, I must prove myself.

The major’s aide is in his tent, already packing. “What can I do for you?” he asks. I explain.

“It’s got to fit in two chests,” he says. “The captain gets his tent, two chests, plus his camp bed, and the collapsible table and stool.” He grins. “You get what you can carry.”

“What does he need? Warm clothes? Do we take the brazier?”

He sits down, waves me to another stool. “Those are good questions. We could be in the mountains. Likely will be.” He blinks, his eyes distant for a moment. “Have some wine?”

I accept. He is older, near retirement, I guess. There will be a story, but listening is a small price to find out what I should pack.

“I fought in Qipërta, twenty years ago, more,” he begins. “When we subdued it. It’s a client kingdom, now.”

“The king still reigns, but Casil governs, yes?” Marcellus has explained this.

“That’s it. It was a long fight. The generals would think it won, but the Qipërtani moved up into the mountains—half the country’s mountains—and hid. Mountain fighting’s hard. So many places for ambushes. Lost a lot of men.” He pauses, sips some wine. “I got there near the end. Casil won by attrition. You know what that means?”

I shake my head.

“We had replacements for the soldiers who died. They didn’t. So they had to surrender, in the end.”

“Why didn’t they ask the Boranoi for help?” I ask. “They’re Casil’s enemy.” It is what boys do, in their wars in the streets of the subura. Sometimes opponents can be allies.

He raises an eyebrow. “You’re quick. But I don’t know. Maybe they did, and the Boranoi said no. Or wanted too much in return. Ask an officer, if you care. What does it matter now?”

What did it? “So I pack warm clothes?”

“And the brazier, and blankets and furs.”

I finish my wine, give him my thanks. Back at the tent I empty the chests, put the winter things at the bottom, divided between the two. Everything that can be divided will be. Trader’s knowledge. One ship, one chest may be lost, but not the other.

I cannot decide which books, or what of his writing materials Marcellus will want. I leave out the shaving equipment, his comb, a cup for wine, a plate. I have done all I can tonight. Outside I can hear laughter, song, the curses of men losing at dice. I am restless. The business of packing occupied me, but now the ache of uncertainty returns. I am going to war. I could die.

As I could on the ships, like Bernikë’s betrothed. Storms, pirates, rocks. An accident on the docks or in the streets.

Or had I been born an unwanted girl.

I push aside the tent flap. Fires flicker, bright in the dark. Marcellus will be gone until morning. I can dice, and drink, and find other distractions beyond the fires. The night has its welcomes.

I fetch bread and olives for Marcellus’s breakfast, ignoring the pain behind my eyes. All I want is water. As he eats, I ask about books. He nods. “I’ll put the ones I want aside. The others should be packed; they’ll go to my wife. I’ve arranged a cart.”

On the training field the sergeant does not care about aching heads and sore stomachs. We practice close combat. My sweat smells sour, like bad wine, like my mouth tastes. The sergeant is merciless this morning, his shouts louder than the ring of blades on shields. I slip on vomit, nearly go down. I turn the slip into a dodge, and come up to ram my shield into my opponent’s arm. He roars in pain, or rage. We stop, staring at each other, panting. I grin, and he does too.

“Enough!” The sergeant. “Line up.”

Go back to our barracks, he tells us. Bring all our gear, our bedding, our packs, everything. Ten minutes. We jog off, straggle back, the older men ahead. They expected this. So did I, alerted by the man I left the fires with last night. My promptness is noted by the sergeant. Good.

“Twenty miles a day,” the sergeant says, once we are all assembled. “Break camp at dawn, march, make camp.” We have practiced this, too, the ditches to be dug, the stakes erected. Most of us will carry a tool for the trenching, and a bundle of stakes for the fence. Not me, though. Marcellus’s needs are my first responsibility. His tent must be raised, his bed set up, water brought. But if I am quick with that, I will go to help make the defences, if Marcellus allows. Men remember such things, and it might matter.

We practice the march. Four abreast, not too close to the man ahead or behind. Not too far, either. Sandals snug, belts as well. Right foot first. We march along the edges of the camp, leather creaking. A shout from among the tents. A running man. The capora, who oversees the cohorts. He stops us.

“Back to your barracks,” he says, between breaths. “Clean up as best you can. Return in full uniform. The Emperor is coming.”

The Emperor? I hear murmurs and curses. “Now!” the capora barks.

We run, weapons bouncing. I think as I go. Marcellus’s armour is clean. His weapons too. My buckles are not, dust and worse from the training ground, my sandals filthy. As am I.

Marcellus is at the tent, already buckling on his greaves. I sluice water over my hands, rub them dry against my tunic, before I kneel to help. “This is purposeful,” he tells me. “He knows we deploy at dawn.”

Supervisors everywhere do this. The warehouse foreman did. My father too would arrive unannounced at the docks. The sergeants here, when we are meant to be cleaning armour and weapons. Emperors are not different, it seems.

I hand Marcellus his helmet. He looks at me. “Wipe the dust off your shield and sword. In formation, the Emperor won’t notice individuals. But he’ll notice the condition of your weapons, and how you stand. Do what your sergeant orders, smartly.” He touches my cheek. “And maybe wash your face.”

I do as he tells me, the weapons first. Then the leather of my uniform, and only then my arms and legs. I wash my face, run hands across my hair, and jog to the training ground. The sentries in the guard towers raise spears in a salute, and the big gates begin to swing open.

We stand in the sun a long time. The sand reflects heat. Lines of bodies add to it. Sweat trickles down my neck. My scalp itches. I shift my weight to my left foot. After a while, back to my right. We are allowed to rest the shields on the ground, at least.

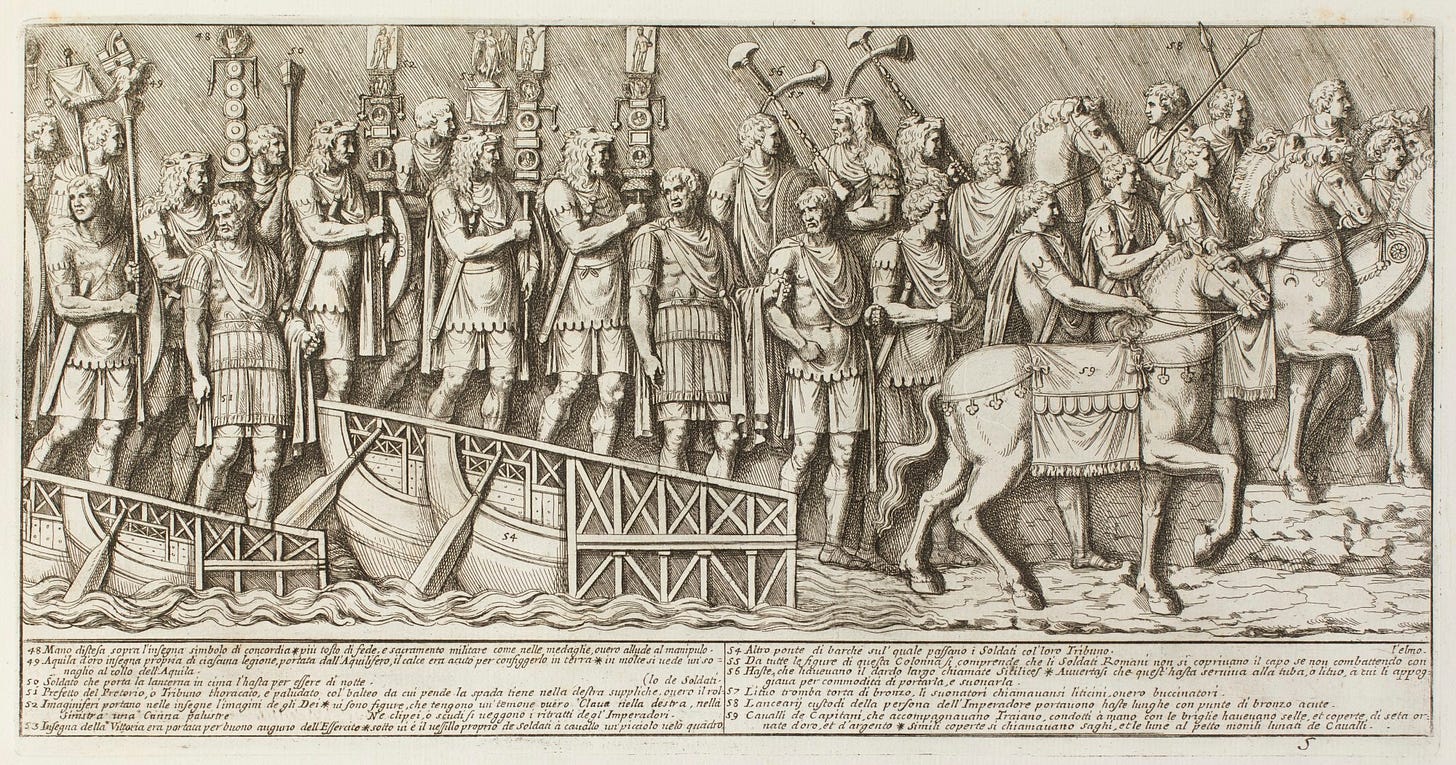

A command from the sergeant, repeated by the capora. We stiffen, raise shields and swords. A tall man, beyond middle age, walks with our commander. He is dressed as a general, but he wears a short cloak of purple too. Behind him, the other officers. Beside him, a boy a year or two younger than me.

We are put through our paces. We advance. We relieve our front rank with the rear. We make shield walls and turtles. I cannot look at the Emperor. I do not want to be the one who stumbles, who turns incorrectly.

Finally we are told to stand at ease. I lower the shield to the ground. My arm aches from holding it high. The Emperor steps forward. “Well done, men,” he says. His voice carries. Still, I am glad I am close to the front. He nods to the standard-bearer in the centre of the first rank, the eagle glittering. “You are to defend the honour of Casil, of the Eastern Empire. My honour, and yours. I have no doubt you will do it well.”

The veterans raise swords, shout his name. I copy them. So do all of us who are new. Three times we do this. The Emperor inclines his head, says something to the boy beside him. His son, I think. Will he be Emperor someday?

Did he want to be? I was meant to be a merchant. I ran away in anger. Princes cannot do that, I guess. We stand, waiting. The Emperor must return to the headquarters before we can move. I think about the boy. He is here to learn. But also to teach us, yes? If I live, I will be a soldier for twenty-five years, more. His father is not young. He was here to be seen. To be recognized. Accepted.

I say this to Marcellus, much later. I sit, knees up, leaning against his bed. It is too narrow for us both, after. His hand plays on my neck, one finger moving up and down. “I suppose he was,” he says slowly. “I hadn’t thought of it that way.” He is quiet a moment. “But Philitos is his father’s heir.”

“The son always succeeds? Not a nephew, or a daughter’s husband?”

“Not in the last hundred years, or more.” He shifts so he is on his side. “Before that, yes. Sometimes even the army declared a general Emperor.”

“So now they show us who is next as soon as he is a man, yes?”

“You may be right.” His fingers still. “It is an astute observation, Druisius.” A new note in his voice. I have surprised him. He sighs and lays back. “We should sleep. Tomorrow will be long and tiring.”

DOCKS ARE DOCKS anywhere, yes? Or so I thought. But it is not true. Even though this town is run by Casil, the harbour is disorganized. To my eyes, anyhow. Or maybe it is just too small for the fleet of ships that brought us here.

At least the horses are being unloaded first. I see Marcellus’s grey being led off by its groom. Its coat is patterned, like light shining through lattice. Dappled. A word he taught me. He is proud of the horse. Much, I think sometimes, as he is proud of me. We are useful to him. We serve a need, and we are handsome, in our own ways. I am not tall, but I have good muscles. I use weapons well. Other men notice both the horse and me.

I have thought, on the voyage. I did not travel with Marcellus on the ships. In close quarters, it is not appropriate, he had said. He did not explain further, but I understood. I could overhear talk among the officers, things I should not know.

So I talked, to recruits and to veterans. Most want nothing but to fight and live. Some speak of the baths, and of women or boys to be had. This city will be no different than Casil in that. Some will seek out poppy or cannabium. They look little further than the next hour, the next day.

But already I know this is not enough. Maybe this is Marcellus’s doing, his talk of rising to be a general. I can be a sergeant, if I prove myself. Even more. Some officers come from the ranks.

My first duty as we disembark is to my captain. I make sure my sergeant sees me, nods when I tell him where I am going. Marcellus is examining his horse’s legs. He straightens, says something to the groom before acknowledging me.

“Druisius. Good voyage?” I tell him yes. I was not seasick, like so many were. He chuckles. “The sea’s in your blood, I suppose. See to my baggage, will you?”

“Where are we going?” I ask, before I go to find the carts.

“A camp outside the city walls. Not a lot to do; the palisade is permanent. Only the tents to get up.”

“Just tonight?” It matters, for firewood and water.

“Two, maybe three nights.” He grins. “Men need to get their land legs, and satisfy some appetites. And there are talks with the governor, for the general.”

There were men on the city walls, watching us arrive. I glance up. Some are still there, some are gone. Are some now riding out of a city gate, with numbers to report?

“The mountains, where we go, they are north, yes?”

“Yes. North and east. Four days march.”

I return to the quay to find Marcellus’s baggage. Then I help the major’s man raise his tent, and then my captain’s. “The Boranoi will know we are coming, and our numbers, yes?” I ask.

“Likely.” He dusts his hands off. “But we’ll know theirs, too. There will have been scouts up at the border, and the general will send his own ahead, too. From his personal guard.” He smirks at me. “Stay close, Druisius. The captain is young, and he’s not had your company for some days. He’ll be looking for you as soon as the general’s briefing is done.”

Scouts. I think about this as I heat water, wash, fill the kettle again for Marcellus when he arrives. A scout would work alone, or in pairs, maybe? Not in a formation of men. No sergeant shouting orders. Dangerous, though. The same for all soldiers.

Only generals have personal guards. Is this what Marcellus intends for me, when he says I will rise with him?